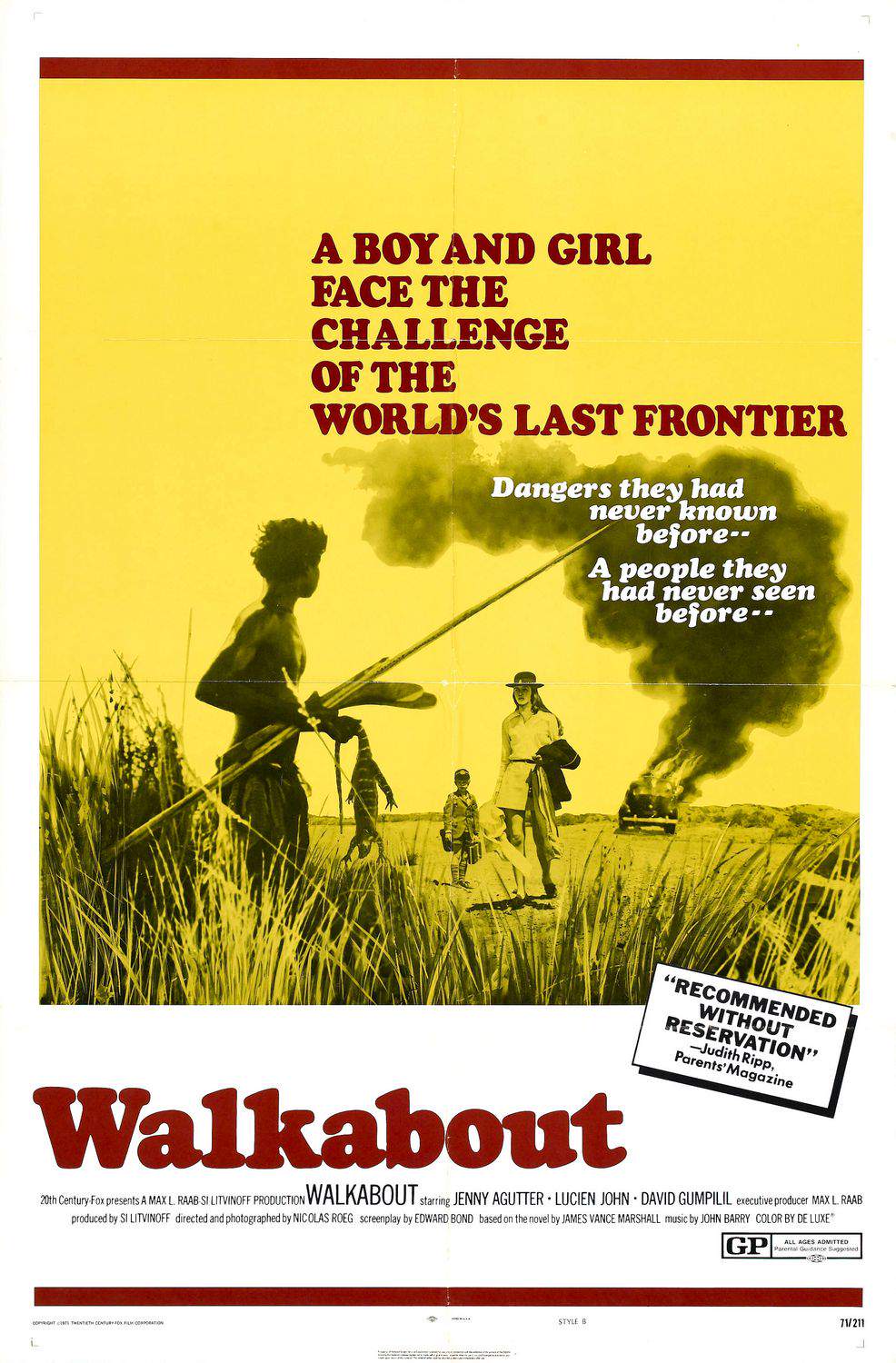

Walkabout 1971

During a wilderness retreat, a group of young Christians encounters unexpected challenges when a novice filmmaker documents their journey. The experience tests their faith and reveals the raw beauty and power of the natural world as they navigate unforeseen circumstances and confront the fragility of their beliefs.

Does Walkabout have end credit scenes?

No!

Walkabout does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of Walkabout

Explore the complete cast of Walkabout, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch Walkabout online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for Walkabout

See how Walkabout is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where Walkabout stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

85

Metascore

8.1

User Score

7.6 /10

IMDb Rating

73

%

User Score

Take the Ultimate Walkabout Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of Walkabout with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

Walkabout Quiz: Test your knowledge on the 1971 film 'Walkabout' and its poignant story of survival and cultural exploration.

Who are the main characters in the film?

Jenny Agutter and her younger brother

Their father and mother

David Gulpilil and the mother

The aborigine and a group of scientists

Show hint

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for Walkabout

Read the complete plot summary of Walkabout, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

Somewhere along the picturesque harbourside of Sydney, Australia, a family resides in a high-rise apartment. The mother bustles in the kitchen, preparing a meal while tuning into the radio. Her fourteen-year-old daughter, Jenny Agutter, and her six-year-old son, Luc Roeg, splash and play in the building’s pool, reveling in the beautiful ocean view. Meanwhile, their father, John Meillon, absorbed in troubled thoughts, watches them from the balcony.

Everything changes one fateful day when the father decides to take his children, still clad in their school uniforms, on a picnic in the Outback. After parking the car, he begins reading while his daughter sets up their lunch on a blanket. The young boy engages in play with his toy soldiers, blissfully unaware of the impending chaos. Suddenly, the father declares it’s time to leave and, brandishing a gun, fires several shots at them. What seems a game to the boy quickly turns into a nightmare, as his sister realizes the peril and instinctively shields him as they run for their lives. Tragedy strikes as she helplessly watches her father return to the car, set it ablaze, and take his own life.

Determined to survive, the girl quickly retrieves their radio, a scarf, and what little food she can carry. The siblings venture into the wilderness, walking for hours under the scorching sun, calmed by the irrelevant radio broadcasts echoing in their minds. As night falls, they establish a makeshift camp, deriving some joy from their surroundings. The next morning, they climb a rocky hillside, but the vast wilderness offers no signs of civilization. To keep their spirits up, the girl tries to ration their meager supplies, recalling stories of her uncle’s survival training while reassuring her brother they are not lost.

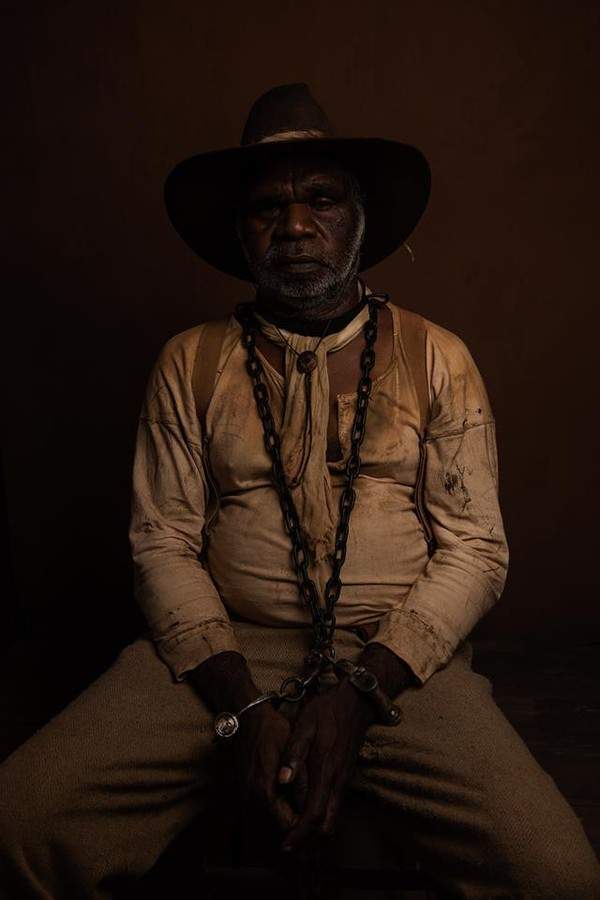

As the days pass, the children discover a lone tree beside a waterhole filled with parakeets, indulging in some much-needed refreshment. However, when they wake one morning to find the waterhole dried up, the girl decides to stay put, hoping the water will return. While they rest in the hot sun, her brother spots David Gulpilil, a young Aboriginal boy, hunting nearby. They attempt to communicate with him, but the language barrier complicates matters. Their need for water becomes evident, and in an unexpected gesture of kindness, the Aboriginal boy shows them how to dig for water using a hollow tube.

Unbeknownst to the siblings, the Aboriginal boy is on a traditional walkabout, a rite of passage undertaken by every young male to mark his transition into adulthood. As they journey through the Outback together, he provides food and sustenance, while the children remain amazed by their new friend. When the boy’s back gets sunburnt, the Aboriginal youth uses pig fat for relief, showcasing an unspoken bond forming among them, despite cultural differences.

The girl’s cautious nature conflicts with the burgeoning feelings the young Aboriginal boy has for her, fostering tension. Attempts at establishing a connection through drawing seem to yield hopeful results, as they share moments of laughter and confusion. Yet as they draw closer to an abandoned homestead, the girl finds herself overwhelmed with nostalgia and sorrow upon discovering relics from a past life, including old photographs.

As the trio continues their journey, they encounter distractions such as a passing truck filled with white men, which leaves the boy perplexed. In an attempt to express himself, the Aboriginal boy performs a courtship dance for the girl, adorned with clay and feathers, but instead of evoking admiration, it instills fear within her. The relationship grows strained as the girl reluctantly decides that they must part ways with their companion in pursuit of safety.

On the following day, clad in their school uniforms, they decide to continue alone. The girl insists the Aboriginal boy has returned to his people, but her brother’s discovery of their friend’s lifeless body, a victim of exhaustion and heartbreak, shatters her naive optimism. They depart from the serene yet haunting scene, seeking help from a nearby mine, where their cries go unanswered.

Years later, the now-grown girl reunites with her husband, who is excited about a promotion leading to a vacation on the Gold Coast. Yet, as he engages her in conversation, her mind wanders back to the carefree days spent in the Outback with her brother and their Aboriginal friend, capturing a fleeting moment of childhood innocence that echoes through time.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

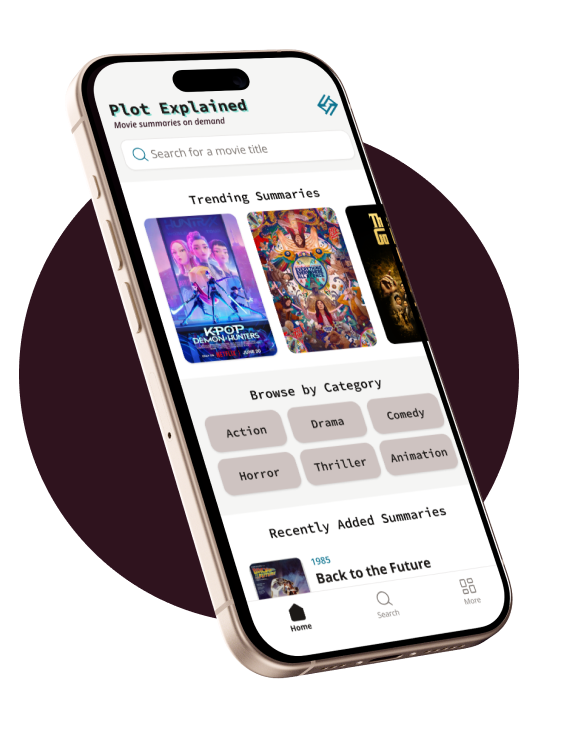

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for Walkabout

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from Walkabout. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Cars Featured in Walkabout

Explore all cars featured in Walkabout, including their makes, models, scenes they appear in, and their significance to the plot. A must-read for car enthusiasts and movie buffs alike.

Walkabout Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

Walkabout Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for Walkabout across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

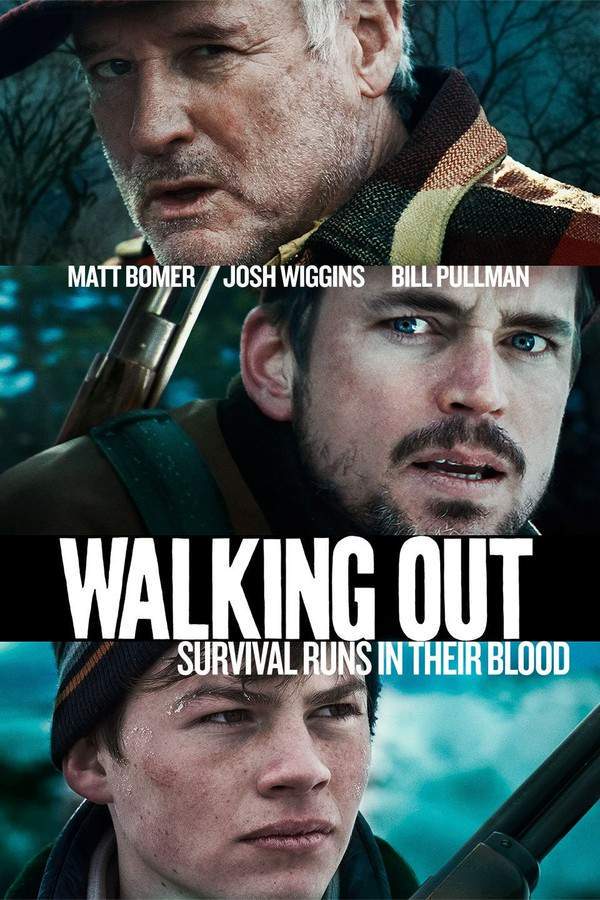

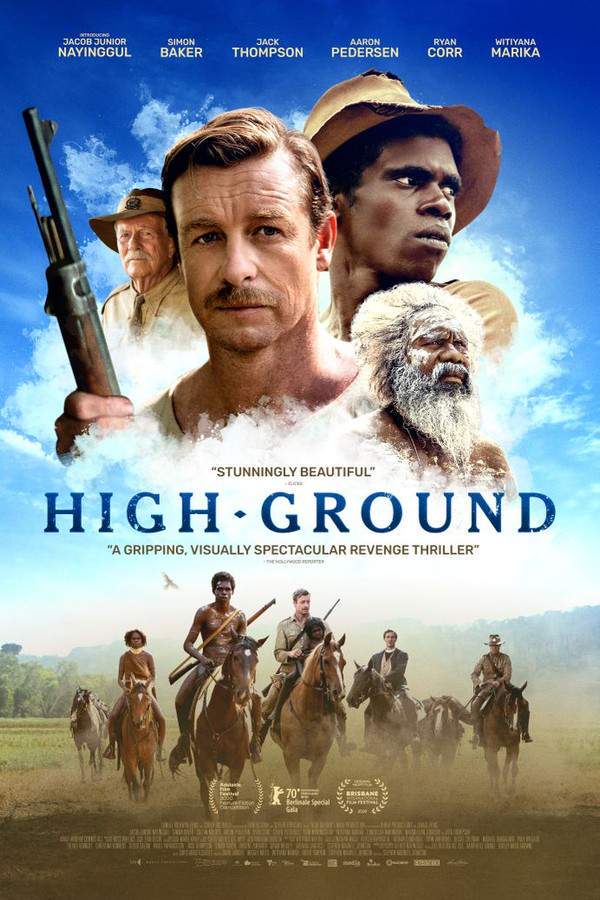

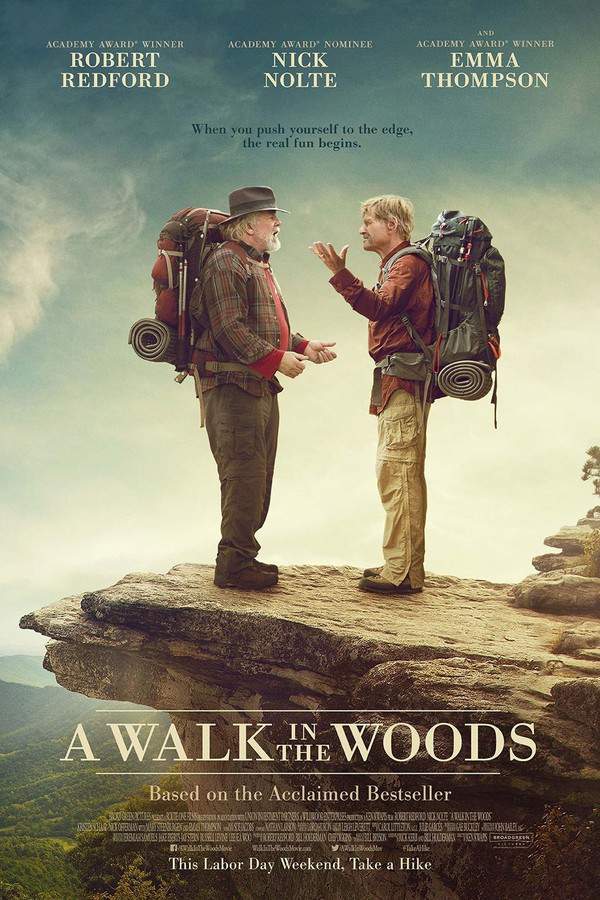

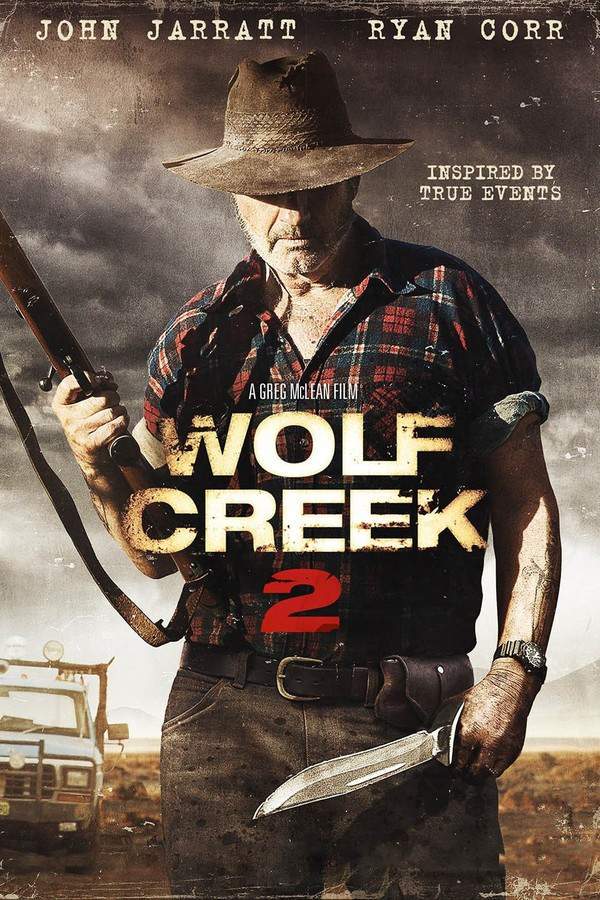

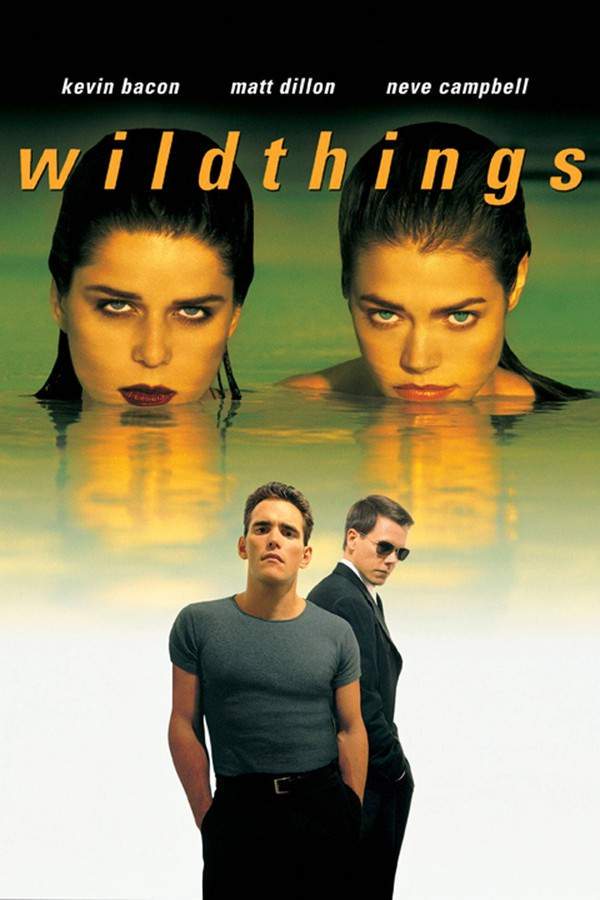

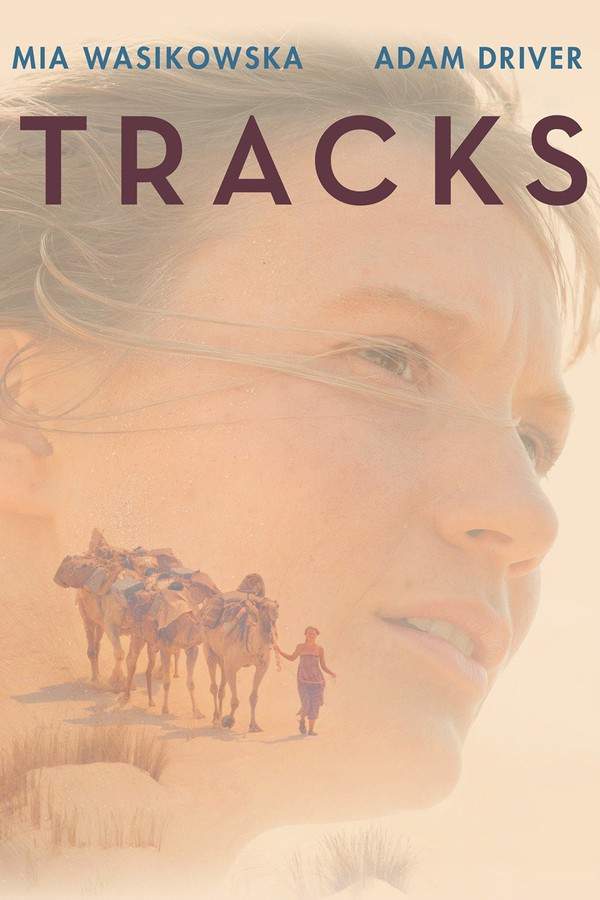

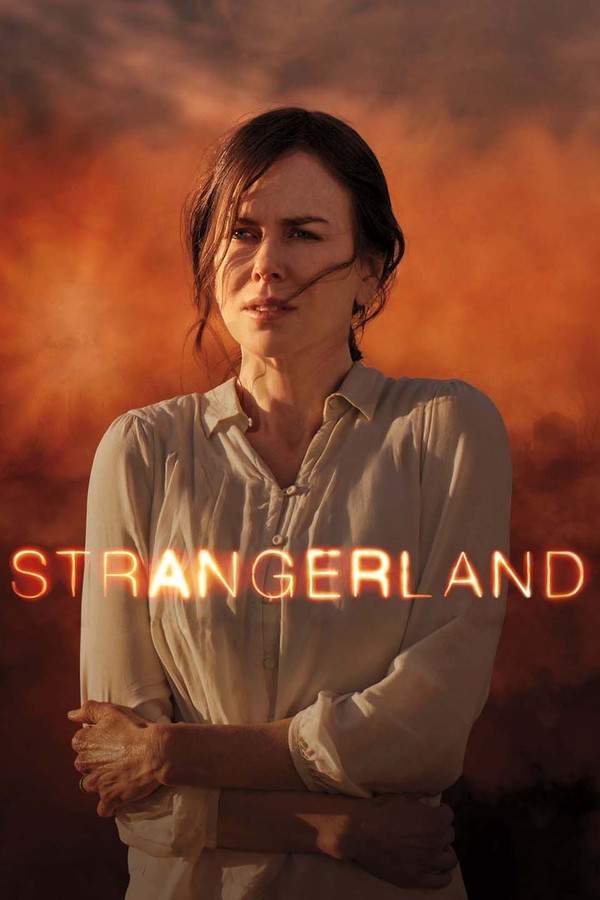

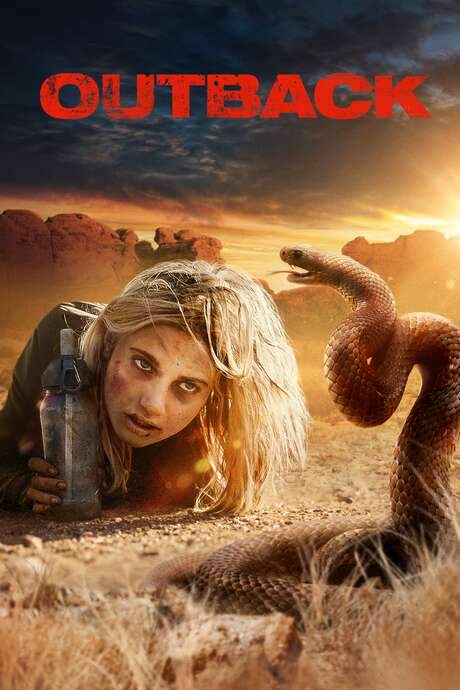

Similar Movies To Walkabout You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.