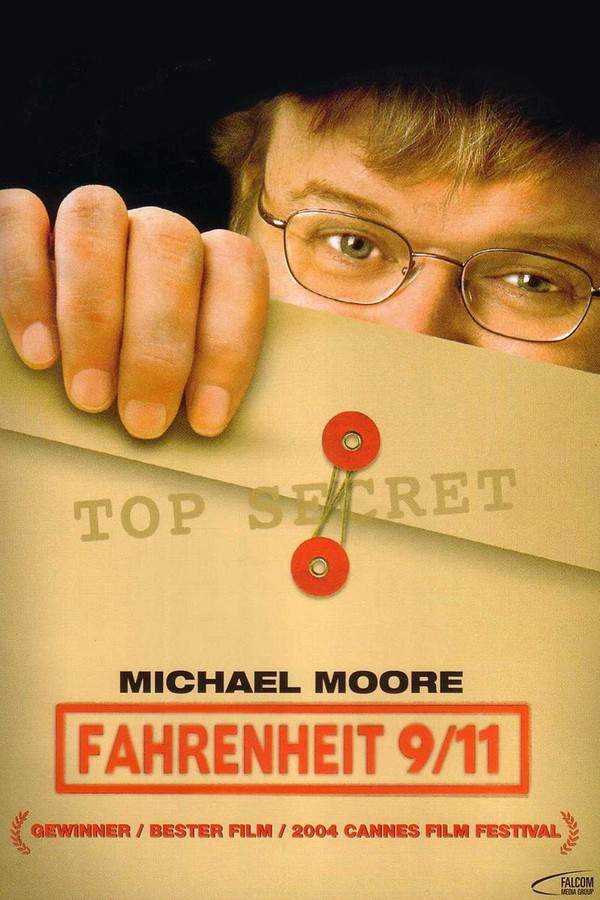

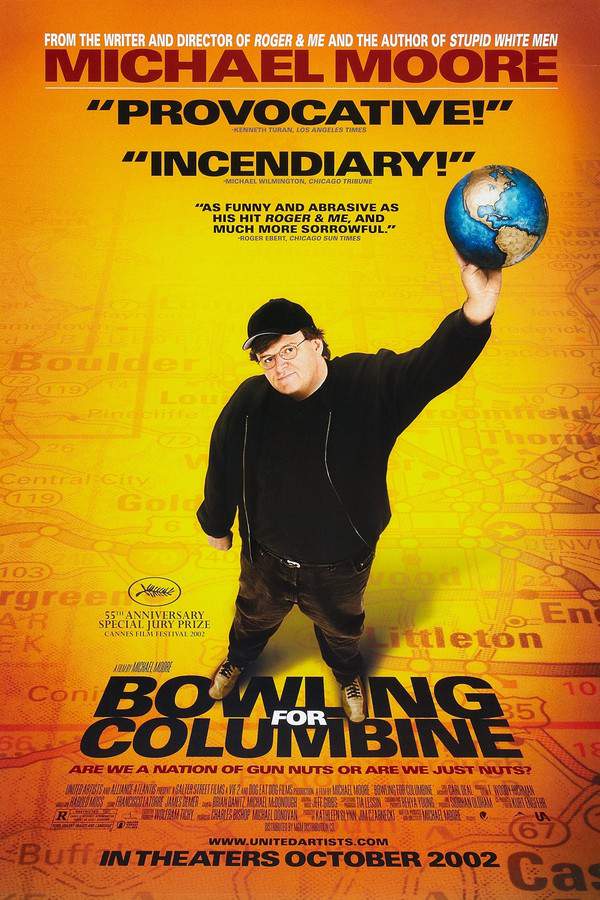

Bowling for Columbine 2002

Michael Moore’s insightful documentary explores the Columbine High School tragedy and investigates the complex factors contributing to the massacre. Through his characteristic blend of humor and pointed questioning, Moore examines America's relationship with firearms, confronting Kmart employees about ammunition sales and contrasting gun violence rates with those in Canada. He also engages in a memorable exchange with actor Charlton Heston regarding his support for the NRA, prompting a thought-provoking discussion about gun ownership and responsibility.

Does Bowling for Columbine have end credit scenes?

No!

Bowling for Columbine does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of Bowling for Columbine

Explore the complete cast of Bowling for Columbine, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

No actors found

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch Bowling for Columbine online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Rotten Tomatoes or Metacritic.

Ratings and Reviews for Bowling for Columbine

See how Bowling for Columbine is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where Bowling for Columbine stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

72

Metascore

7.4

User Score

95%

TOMATOMETER

83%

User Score

8.0 /10

IMDb Rating

75

%

User Score

Take the Ultimate Bowling for Columbine Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of Bowling for Columbine with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

Bowling for Columbine Quiz: Test your knowledge on Michael Moore's thought-provoking documentary that explores gun culture and violence in America.

What pivotal event does Bowling for Columbine primarily address?

9/11 attacks

Columbine High School massacre

Virginia Tech shooting

Oklahoma City bombing

Show hint

Awards & Nominations for Bowling for Columbine

Discover all the awards and nominations received by Bowling for Columbine, from Oscars to film festival honors. Learn how Bowling for Columbine and its cast and crew have been recognized by critics and the industry alike.

75th Academy Awards 2003

Documentary (Feature)

8th Critics' Choice Awards 2003

Best Documentary Feature

18th Film Independent Spirit Awards 2003

Best Documentary Feature

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for Bowling for Columbine

Read the complete plot summary of Bowling for Columbine, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

In Michael Moore’s provocative documentary, he engages in discussions with notable figures such as South Park co-creator Matt Stone, musician Marilyn Manson, and then-president of the NRA Charlton Heston to uncover the underlying reasons behind the Columbine massacre and the alarmingly high rate of violent crimes in the United States, particularly those involving firearms.

The film’s title derives from a chilling detail regarding Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the two students behind the tragic Columbine High School shooting on April 20, 1999. It was initially reported that they attended a bowling class early on that fateful day before commencing their attack, but later investigations revealed they were actually absent from school. Nonetheless, Michael Moore cleverly weaves the bowling theme throughout the narrative. For instance, he captures Michigan militia members practicing with bowling pins as targets. When reflecting on former classmates, Moore learns that Harris and Klebold participated in a bowling class instead of traditional physical education classes, and the girls he interviews generally agree that their interest in bowling held little educational value. This opens a critical discussion about whether educational systems address the genuine needs of the youth, or instead, perpetuate an environment of fear.

Furthermore, Moore ventures to Oscoda, Michigan, where he discovers that firearms are alarmingly easy to access in this small town, particularly since Eric Harris spent part of his childhood there while his father was serving in the Air Force. He goes on to compare gun ownership and violence in various countries, ultimately concluding that there is no direct correlation between gun ownership and violence. In his quest to decipher America’s obsession with guns, Moore identifies a pervasive culture of fear instigated by governmental practices and media portrayals. He sarcastically proposes the idea that bowling could potentially bear as much blame for the tragic events as Marilyn Manson, or even Bill Clinton, who was overseeing foreign bombing campaigns at the same time.

One striking encounter unfolds when Moore visits a Michigan bank that offers a free hunting rifle to customers who meet specific deposit criteria. In a humorous yet unsettling moment, he asks, “Do you think it’s a little dangerous handing out guns at the bank?” After successfully acquiring a gun post-background check, his bewilderment underscores the film’s critique of American attitudes toward gun possession.

As the documentary progresses, it includes poignant montages paired with powerful soundtracks. For example, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” by The Beatles accompanies a chilling sequence depicting various acts of violence and gun ownership in America. Later on, Moore tackles the concept of institutionalized violence through his dialogue with Evan McCollum of Lockheed Martin, effectively linking the local defense industry’s presence to the mentality surrounding the Columbine incident, questioning if children connect missile manufacturing with school shootings.

The film also juxtaposes the fear-based gun culture in the United States with a more peaceful environment in Canada, where gun ownership is similarly prevalent yet incidences of gun violence are remarkably lower. Interspersed with poignant interviews, the documentary serves to illustrate how different cultural contexts shape attitudes toward violence.

Towards the climax, Moore’s conversation with Charlton Heston stands out as he challenges Heston on the NRA’s stance concerning gun violence. Heston’s insistence on the right to bear arms and his defense of the NRA leads to a tense and revealing exchange, culminating in Heston asking the filmmaker and his crew to leave his home.

Through a blend of investigative commentary and societal critique, Moore’s documentary holds a mirror to America’s gun culture, challenging viewers to confront the deep-rooted fears and ideologies that contribute to this ongoing crisis.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for Bowling for Columbine

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from Bowling for Columbine. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Bowling for Columbine Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

Bowling for Columbine Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for Bowling for Columbine across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

Articles, Reviews & Explainers About Bowling for Columbine

Stay updated on Bowling for Columbine with in-depth articles, critical reviews, and ending explainers. Explore hidden meanings, major themes, and expert insights into the film’s story and impact.

Similar Movies To Bowling for Columbine You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.