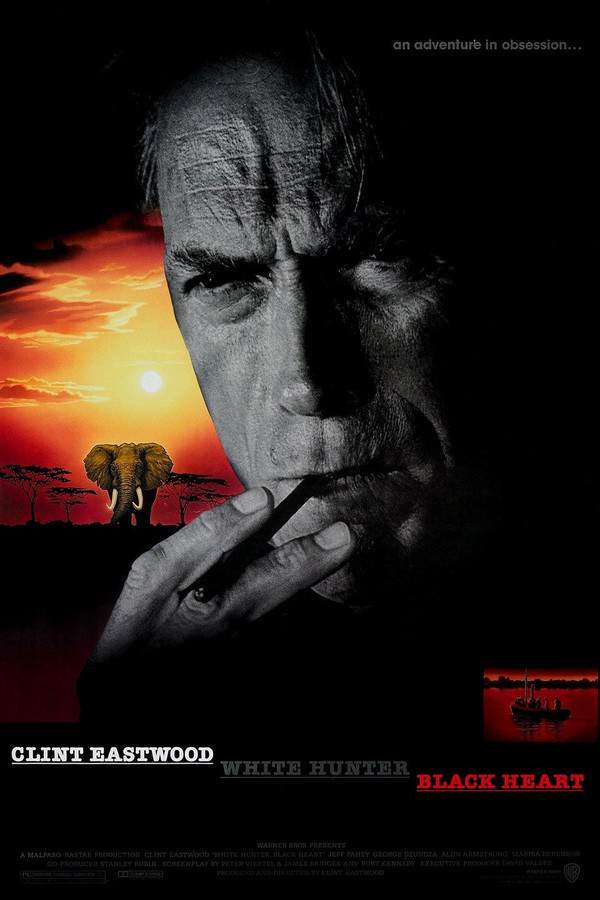

White Hunter Black Heart 1990

In 1950s Zimbabwe, a driven film director, John Wilson, and his screenwriter, Pete Verrill, journey into the wilderness to shoot a film. Wilson becomes obsessed with filming a magnificent elephant, pushing himself and his crew to extreme lengths. As they venture deeper, the pursuit of the perfect shot tests the boundaries of Wilson's artistic vision and forces him to grapple with the ethical implications of his actions.

Does White Hunter Black Heart have end credit scenes?

No!

White Hunter Black Heart does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of White Hunter Black Heart

Explore the complete cast of White Hunter Black Heart, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch White Hunter Black Heart online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for White Hunter Black Heart

See how White Hunter Black Heart is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where White Hunter Black Heart stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

66

Metascore

7.0

User Score

%

TOMATOMETER

0%

User Score

Take the Ultimate White Hunter Black Heart Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of White Hunter Black Heart with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

White Hunter Black Heart Quiz: Test your knowledge on the film White Hunter Black Heart and its intricate themes and characters.

Who is the renowned director that invites Pete Verrill to work on his latest project?

John Wilson

Paul Landers

Ralph Lockhart

Zibelinsky

Show hint

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for White Hunter Black Heart

Read the complete plot summary of White Hunter Black Heart, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

As the early 1950s unfolded, Pete Verrill found himself receiving an unexpected invitation from an old friend, John Wilson, the celebrated director behind The African Trader. Wilson’s persuasive pitch managed to sway producer Paul Landers into making a bold decision: to film the entire project on location in Africa, accepting the steep costs involved. However, unbeknownst to everyone else, Wilson’s real motive was not the film’s success but his deep-rooted passion for African safaris—a desire so intense that he even splurged on an impressive collection of finely crafted hunting rifles, conveniently billed to the studio.

Upon reaching Entebbe, Wilson and Verrill settled into a lavish hotel for several days while Verrill worked on finalizing the script and Wilson prepared for his much-anticipated safari. Verrill couldn’t help but appreciate Wilson’s unapologetic character, which was evident when he stood up for Verrill against a guest’s antisemitic insults, as well as when he confronted the hotel manager over his unjust treatment of a black waiter. A series of animated discussions ensued, particularly regarding Verrill’s insistence that Wilson reconsider his initial vision of a grisly ending where the principal characters faced their doom.

Soon, Wilson employed a pilot to ferry himself and Verrill to the hunting camp of safari guide Zibelinsky and his tracker Kivu. It was here that Wilson quickly forged a connection with the pair, much to Verrill’s frustration. The film’s unit director, Ralph Lockhart, also made an appearance, stressing the need for Wilson to kick off pre-production before the cast’s arrival—a suggestion that flared up Wilson’s typical disregard as he obsessively sought after a prized “tusker”. As the absurdity of Wilson’s antics became clearer to Verrill, doubts swirled in his mind about the morality of hunting such magnificent creatures.

Tensions boiled over between Wilson and Verrill, culminating in a pointed attack from Wilson who accused Verrill of playing it too safe and avoiding risks. Wilson’s harsh evaluation of hunting as a “sin that can be licensed” met with a cold silence from Verrill, who ultimately faced an ultimatum: stay on the project or return to London. Meanwhile, Landers came to Entebbe brandishing dire news—the looming threat of bankruptcy if the film’s completion faltered. Upon returning, Verrill encountered a shocking revelation from Lockhart: Wilson had rashly decided to shift the entire production to Kivu’s village, despite Landers’ careful allocation of funds for a set.

As the cast and crew begrudgingly departed their hotel, they arrived at Zibelinsky’s camp, welcomed by an extravagant feast that Wilson had arranged. Despite the opulence, the mood was strained, with Landers experiencing public humiliation while Wilson seized the moment to thrive in his safari pursuits. Responding to Wilson’s jibes of cowardice, Verrill reluctantly chose to join. However, when Wilson finally had the chance to take down the enormous tusker, he hesitated, unable to pull the trigger. The elephant, sensing her young nearby, charged, and Kivu’s brave attempt to intervene turned fatal as he fell victim to the tusker’s deadly tusks.

Consumed by guilt and horror over Kivu’s tragic fate, Wilson returned to the set to find a somber air hanging heavily over everyone. The rhythmic drumming from the villagers underscored the weight of what had happened: “white hunter, black heart.” Recognizing his role in the tragedy, Wilson turned to Verrill, acknowledging that the film indeed needed a happier conclusion. As he settled back into his director’s chair, beset by the anticipatory energy of the crew and actors gearing up for the first scene of The African Trader, Wilson’s earlier bravado gave way to a sobering sense of reflection, punctuated only by his quiet instruction: > “Action.”

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for White Hunter Black Heart

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from White Hunter Black Heart. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Cars Featured in White Hunter Black Heart

Explore all cars featured in White Hunter Black Heart, including their makes, models, scenes they appear in, and their significance to the plot. A must-read for car enthusiasts and movie buffs alike.

White Hunter Black Heart Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

White Hunter Black Heart Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for White Hunter Black Heart across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

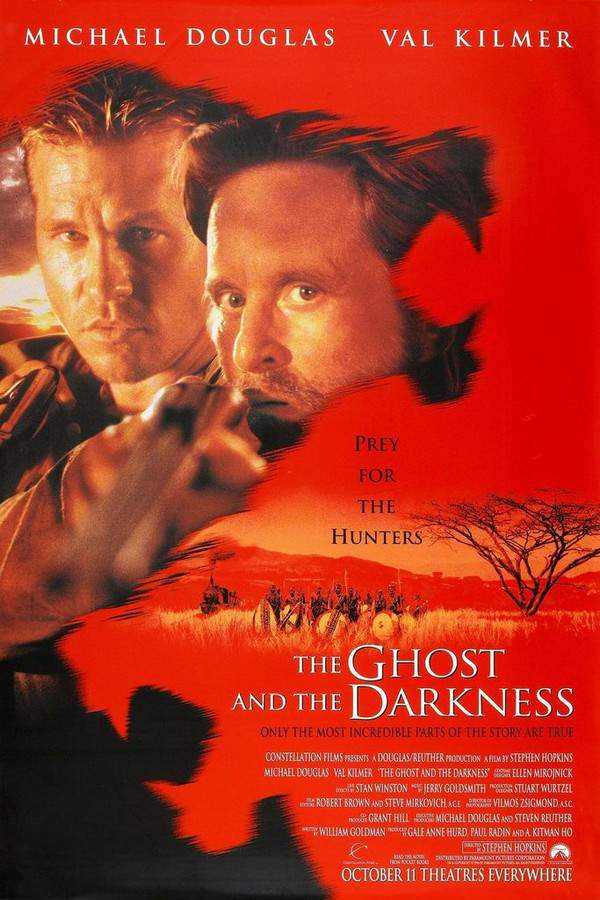

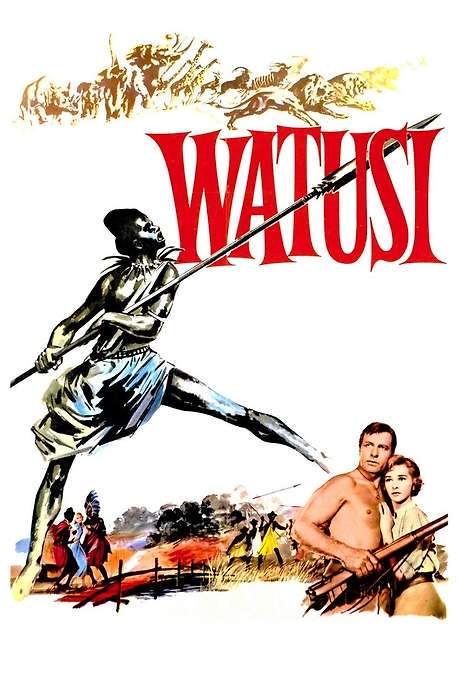

Similar Movies To White Hunter Black Heart You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.