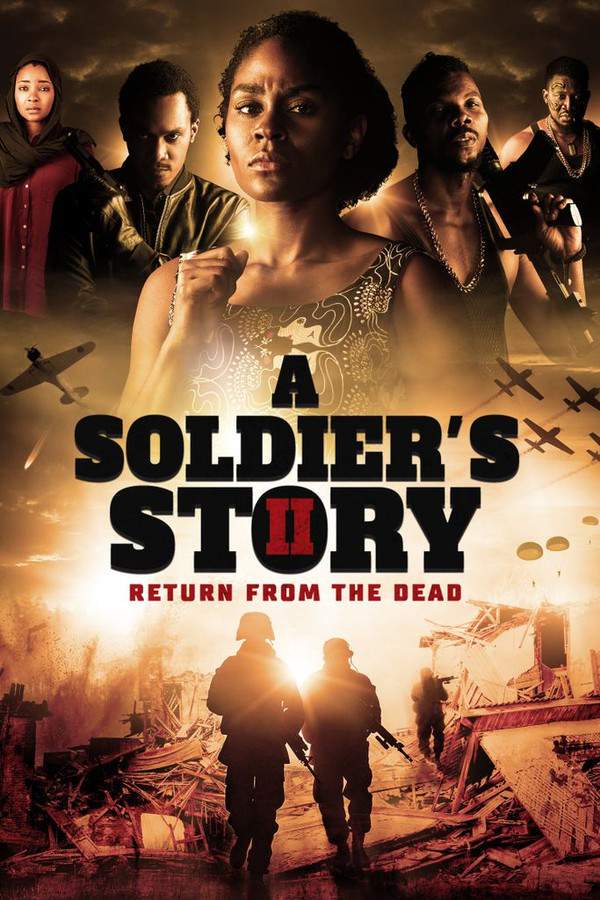

A Soldier's Story 1984

Following a devastating war in the Watz Republic, Regina entrusts her friend Zaya with the care of her brother before embarking on a journey to Nigeria with her fiancé, Major Egan. Their trip is abruptly threatened when they become the targets of a dangerous assassination attempt. They must then fight to protect themselves and uncover the dark conspiracy behind the attack, revealing the sinister forces at play.

Does A Soldier's Story have end credit scenes?

No!

A Soldier's Story does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of A Soldier's Story

Explore the complete cast of A Soldier's Story, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch A Soldier's Story online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for A Soldier's Story

See how A Soldier's Story is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where A Soldier's Story stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

66

Metascore

6.2

User Score

68

%

User Score

Take the Ultimate A Soldier's Story Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of A Soldier's Story with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

A Soldier's Story Quiz: Test your knowledge of the poignant narrative and themes explored in the 1984 film 'A Soldier's Story'.

What year does the film 'A Soldier's Story' take place?

1942

1944

1945

1943

Show hint

Awards & Nominations for A Soldier's Story

Discover all the awards and nominations received by A Soldier's Story, from Oscars to film festival honors. Learn how A Soldier's Story and its cast and crew have been recognized by critics and the industry alike.

The 57th Academy Awards 1985

Best Picture

Writing (Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium)

37th Directors Guild of America Awards 1985

42nd Golden Globe Awards 1985

Best Motion Picture – Drama

Best Supporting Performance in a Motion Picture – Drama, Comedy or Musical (Supporting Actor)

Adolph CaesarBest Screenplay

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for A Soldier's Story

Read the complete plot summary of A Soldier's Story, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

As the pivotal year of 1944 unfolded during World War II, Master Sergeant Vernon Waters met his untimely demise in a hail of bullets just outside Fort Neal, a segregated Army base located in Louisiana. The echoes of his heart-wrenching cry, > “No matter what you do, they still hate you!” — continue to resonate, haunting the scene where he fell victim to a .45 caliber pistol. In response to this senseless act of violence, Captain Richard Davenport, a dedicated officer from the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, was assigned to investigate the circumstances surrounding this tragic event, much to the dismay of Colonel Nivens.

Initial speculation suggested that Waters had been targeted by the local Ku Klux Klan, but doubts quickly surfaced regarding the validity of this assumption. Colonel Nivens granted Davenport a mere three days to conduct his inquiry, a challenge compounded by the reluctance of Captain Taylor, the only white officer who shared Davenport’s commitment to seeking justice. Taylor, struggling with the reality of a Black officer leading the investigation, provided little more than condescending patronage rather than genuine cooperation. This tension left the Black soldiers feeling divided; some took pride in seeing one of their own in a captain’s role, while others remained wary and evasive.

As Davenport delved deeper into the case, he stumbled upon a critical detail that contradicted the prevailing narrative: unlike other Black soldiers slain by the Klan, Waters’ body was discovered still adorned in his military uniform. This discrepancy ignited fresh inquiries about the true nature of his death.

The 221st Chemical Smoke Generator Battalion, the unit to which Waters belonged, had been relegated to menial tasks on the Home Front despite their fervent desire to engage in combat. Comprising former stars of the Negro baseball leagues, the team had garnered fame under Waters’ managerial leadership, even generating buzz about a potential exhibition game against the New York Yankees.

James Wilkie, a former sergeant and acquaintance of Waters, painted a complex portrait of the late soldier. A veteran of World War I, Waters had been awarded the Croix de Guerre by the Third French Republic for his valor and was remembered as a strict yet fair non-commissioned officer, earning the respect of his men, particularly C.J. Memphis, the talented pitcher and jazz musician of the unit.

Yet, as Private Peterson began to uncover the malevolent side of Sergeant Waters, he was taken aback by the officer’s disdain for African American soldiers from rural Southern backgrounds who lacked formal education or communicated in the Gullah dialect. Peterson recounted a harrowing encounter where he stood up to Waters after being berated post-victory, only to be brutally assaulted in retaliation. This trauma lingered in Peterson’s mind as he recounted the incident to Lieutenant Davenport.

Continuing his probe, Davenport interviewed fellow soldiers, including Corporal Bernard Cobb, who was also brought in as a murder suspect. Cobb disclosed that Waters had previously visited C.J. in the brig, bragging about a framing plot he had executed before. To Waters, uneducated and subservient Southern Blacks like C.J. represented an obstacle to racial equality, leading him to believe that they should be removed at any cost.

As the investigation deepened, Davenport unearthed a heartbreaking tale of desperation and claustrophobia. Cobb recounted how C.J. had long struggled with confinement and eventually tragically took his own life while awaiting court-martial. In mourning for their teammate, the baseball team chose to forfeit their final game, leaving Waters unsettled. Subsequently, Captain Taylor disbanded the team and reassigned its members, sending Waters into a downward spiral.

In the meantime, racist white officers Captain Wilcox and Lieutenant Byrd confronted Waters shortly before his death. Both officers confessed to assaulting him after he succumbed to a drunken outburst but claimed they refrained from killing him due to limitations on their issued firearms. While they asserted their innocence and submitted their weapons after the incident, Captain Taylor labeled them as murderers, whereas Lieutenant Davenport ultimately cleared them of wrongdoing.

As Davenport delved deeper into the mystery surrounding Sgt. Waters’ murder, he uncovered a convoluted web of lies and racial hatred. During intense questioning, Wilkie divulged that Waters had instructed him to plant the incriminating weapon at C.J.’s quarters, motivated by an entrenched animosity toward Gullah-speaking Southern Blacks like C.J. This vendetta originated from a traumatic episode in World War I, wherein a Black soldier from their unit was subjected to relentless mocking and brutal treatment by racist white comrades in a humiliating incident at the Cafe Napoleon. This long-standing humiliation ignited a devastating spiral of violence as Waters and his fellow Black soldiers sought vengeance.

As Wilkie’s confessions unfolded, Davenport pressed for clarity on why Waters had not similarly framed Peterson after their altercation. Wilkie countered that Waters respected Peterson for his English proficiency and self-worth. This revelation led to Wilkie’s arrest just as the 221st Infantry Regiment prepared for its impending overseas deployment.

The investigation took a pivotal twist when Davenport questioned Smalls, who confessed to witnessing Peterson shoot Waters with a .45 caliber sidearm, rationalizing it as an act of “justice” for C.J. and all Black individuals. As the truth began to unfurl, Peterson maintained a smug demeanor, asserting that he had simply removed those he deemed “unfit” to be Black. Seizing the moment, Captain Davenport confronted Peterson, challenging him on the authority he believed he had to determine another individual’s worth as a Black person.

Following these startling revelations, Major Taylor lauded Davenport for his successful arrests, recognizing that the military would have to adapt to the inclusion of commissioned Black officers. With unwavering determination, Davenport affirmed, “You’ll have to get used to it, and you can bet your ass on that.” As the platoon geared up for deployment in the European theater, the weight of their experiences and the stark realities of war hung heavily in the balance.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

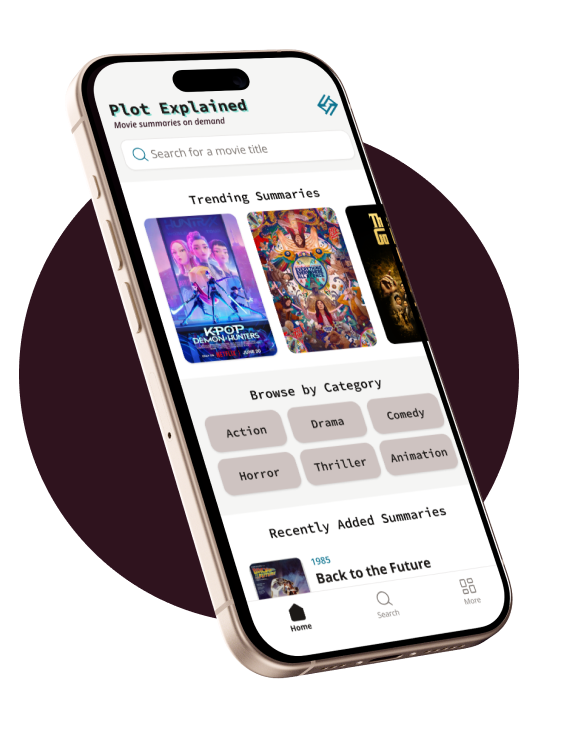

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for A Soldier's Story

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from A Soldier's Story. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Cars Featured in A Soldier's Story

Explore all cars featured in A Soldier's Story, including their makes, models, scenes they appear in, and their significance to the plot. A must-read for car enthusiasts and movie buffs alike.

A Soldier's Story Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

A Soldier's Story Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for A Soldier's Story across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

Similar Movies To A Soldier's Story You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.