Inside Job 2010

This gripping documentary examines the causes and consequences of the 2008 global financial crisis. Through extensive interviews with bankers, politicians, and economists, it explores the systemic failures and questionable practices that led to the crisis, which cost trillions of dollars and impacted economies worldwide. The film investigates the complex relationships between the financial industry, government regulation, and academic institutions, revealing the human cost of unchecked ambition and risky behavior.

Does Inside Job have end credit scenes?

No!

Inside Job does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of Inside Job

Explore the complete cast of Inside Job, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch Inside Job online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for Inside Job

See how Inside Job is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where Inside Job stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

88

Metascore

8.3

User Score

98%

TOMATOMETER

91%

User Score

8.2 /10

IMDb Rating

77

%

User Score

Take the Ultimate Inside Job Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of Inside Job with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

Inside Job Quiz: Test your knowledge on the documentary 'Inside Job' and the factors leading to the 2008 financial crisis.

What main event does the film 'Inside Job' analyze?

Dot-com bubble

2008 global financial meltdown

Enron scandal

Great Depression

Show hint

Awards & Nominations for Inside Job

Discover all the awards and nominations received by Inside Job, from Oscars to film festival honors. Learn how Inside Job and its cast and crew have been recognized by critics and the industry alike.

83rd Academy Awards 2011

Documentary (Feature)

16th Critics' Choice Awards 2011

Best Documentary Feature

63rd Directors Guild of America Awards 2011

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for Inside Job

Read the complete plot summary of Inside Job, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

The documentary Inside Job delves into the 2008 global financial crisis, meticulously analyzing its roots and consequences. It presents a well-researched narrative, illuminated through extensive interviews with a range of experts, including financiers, politicians, journalists, and academics, all divided into five thoughtful segments.

The film emphasizes the radical shifts in the financial sector during the decade leading up to the crisis, spotlighting a political shift towards deregulation. This deregulation paved the way for complex trading mechanisms, such as the derivatives market, which significantly heightened risk-taking behavior, thereby bypassing older regulatory frameworks designed to mitigate systemic risk. As the narrative unfolds, it highlights various conflicts of interest within the financial sector, suggesting that many of these issues remain inadequately disclosed to the public.

A central theme explored is the immense pressure exerted by the financial industry on political processes to stave off regulation. The film scrutinizes the ubiquitous revolving door phenomenon, where financial regulators transition to lucrative positions within the financial sector upon leaving government roles. This practice raises serious questions about the impartiality and integrity of financial oversight.

Within the derivatives market, it is revealed that the initial high risks linked to subprime lending were subtly transferred among investors. Thanks to questionable credit rating practices, investors were misled into perceiving these high-risk investments as secure. Consequently, lenders incentivized to approve mortgages were often blind to the inherent risks, preferring high-interest loans. Following the packaging of these mortgages, the risks became obscured. Astonishingly, these products often attained AAA ratings, comparable to U.S. government bonds, which opened them up to a range of investors, including retirement funds bound to invest only in low-risk securities.

Additionally, the film critiques the skyrocketing compensation in the financial world, which has diverged dramatically from the overall economic growth witnessed in recent decades. Even at institutions that collapsed during the crisis, executives were reportedly pocketing hundreds of millions of dollars leading up to that tumultuous period. The film suggests that the balance between risk and benefit within the industry has profoundly eroded.

Another critical aspect touched upon in the documentary is the role of academia in facilitating the crisis. Notably, it raises concerns about Martin Feldstein, a Harvard economist and former head of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Ronald Reagan, who served as a director for AIG and was intricately linked to influential financial institutions such as J.P. Morgan. Additionally, it dissects how leading faculty members in economics and business schools derive substantial income from consulting and speaking engagements, with figures like Glenn Hubbard, the current dean of the Columbia Business School, receiving a significant part of his earnings from these activities. Despite these insights, Hubbard and others, such as John Y. Campbell, chair of Harvard’s economics department, defend the notion that no conflict of interest exists between academia and the financial sector.

Ultimately, the film concludes with a stark warning: despite the implementation of new financial regulations, the core structural problems remain largely unaddressed. The remaining banks have only grown larger, the underlying incentive structures remain unchanged, and shockingly, no high-ranking executives have faced prosecution for their part in the catastrophic financial collapse.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

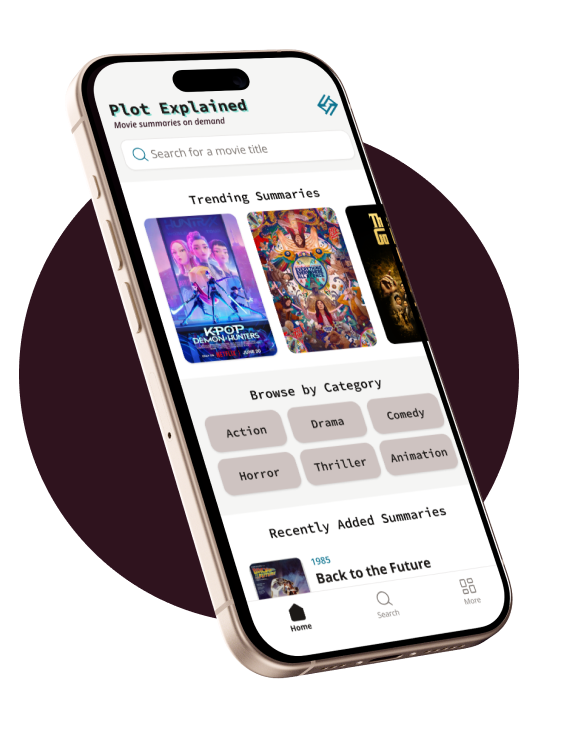

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for Inside Job

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from Inside Job. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Cars Featured in Inside Job

Explore all cars featured in Inside Job, including their makes, models, scenes they appear in, and their significance to the plot. A must-read for car enthusiasts and movie buffs alike.

Inside Job Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

Inside Job Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for Inside Job across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

Similar Movies To Inside Job You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2026)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2026 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.