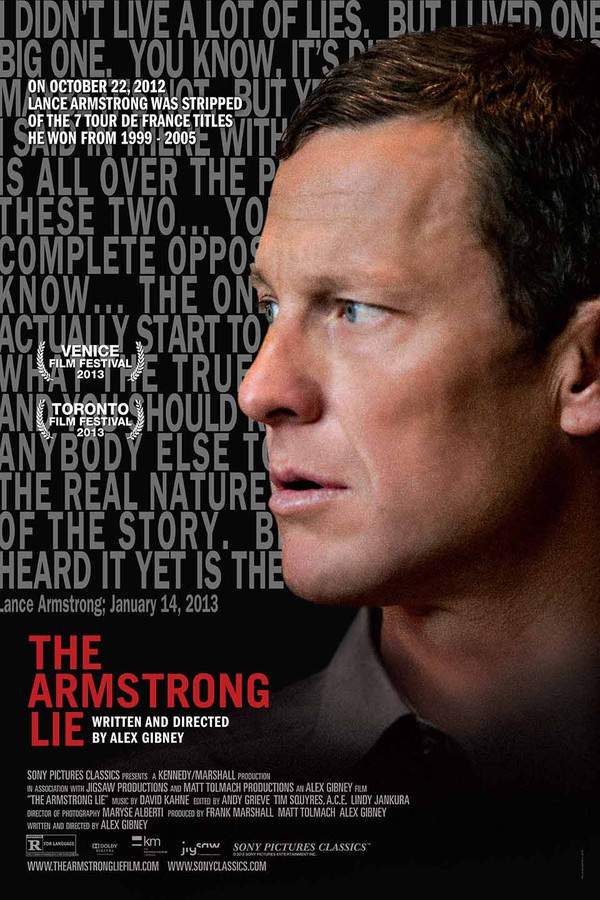

The Armstrong Lie 2013

This documentary examines the career of cyclist Lance Armstrong, charting his remarkable rise to fame and subsequent dramatic downfall. Through interviews and archival footage, the film explores the complexities of his story, revealing a web of deception and the devastating consequences of his actions. It's a candid look at ambition, redemption, and the darker side of athletic achievement.

Does The Armstrong Lie have end credit scenes?

No!

The Armstrong Lie does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of The Armstrong Lie

Explore the complete cast of The Armstrong Lie, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch The Armstrong Lie online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for The Armstrong Lie

See how The Armstrong Lie is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where The Armstrong Lie stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

67

Metascore

7.5

User Score

82%

TOMATOMETER

76%

User Score

7.2 /10

IMDb Rating

69

%

User Score

3.6

From 3 fan ratings

3.67/5

From 3 fan ratings

Take the Ultimate The Armstrong Lie Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of The Armstrong Lie with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

The Armstrong Lie Quiz: Test your knowledge about the highs and lows of Lance Armstrong's cycling career as depicted in 'The Armstrong Lie'.

What was the original title of the documentary directed by Alex Gibney before it was renamed?

The Road Back

Back on Track

Cycle of Lies

Chasing Redemption

Show hint

Awards & Nominations for The Armstrong Lie

Discover all the awards and nominations received by The Armstrong Lie, from Oscars to film festival honors. Learn how The Armstrong Lie and its cast and crew have been recognized by critics and the industry alike.

67th British Academy Film Awards 2014

Best Documentary

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for The Armstrong Lie

Read the complete plot summary of The Armstrong Lie, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

In 2009, director Alex Gibney embarked on a mission to create The Road Back, a documentary that focused on cyclist Lance Armstrong and his comeback during a pivotal year following a four-year hiatus from the sport. However, three years later, a doping investigation led to a shocking revelation in October 2012: Armstrong faced a lifetime ban from competition, and all seven of his esteemed Tour de France titles were stripped away, forcing the documentary to be shelved indefinitely. It wasn’t until January 14, 2013, just hours after his highly publicized interview with Oprah Winfrey, that Armstrong returned to Gibney to clarify the misconceptions surrounding his illustrious yet tumultuous career.

Armstrong’s journey began much earlier, marked by a devastating cancer diagnosis that forced him to step away from professional cycling. Before his illness, he had firmly established himself as a dominant force, winning the prestigious Tour de France seven times, all while facing persistent doping allegations that haunted him throughout his career. By 2012, these accusations had permeated mainstream media to the point where Armstrong could no longer keep his defenses intact. Several of his former teammates came forward to testify against him, asserting they had witnessed his drug use firsthand. Consequently, the UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) banned him from cycling and retroactively stripped him of his titles in October 2012, setting the stage for his notorious Oprah interview in January 2013. During this candid admission, Lance confessed to using performance-enhancing drugs throughout each of his Tour de France victories and regretted his return to cycling in 2009, a comeback that ultimately contributed to his fall from grace.

The implications of Armstrong’s actions were compounded by the UCI’s long-held belief that he had cheated throughout his career. A French article titled The Armstrong Lie highlighted the alarming discovery that his urine samples from his first Tour de France win in 1999 contained EPO, a banned performance enhancer. Interestingly, the UCI permitted Armstrong to compete in the Tour de France in 2009, despite evidence suggesting misconduct. In 2006, a significant doping crackdown implicated 58 cyclists, including each of those who had shared the podium with Armstrong from 1999 to 2005, yet he escaped scrutiny due to his retirement the previous year.

Before making his mark on the cycling world, Lance Armstrong faced a daunting battle with testicular cancer that had spread aggressively by 1999. His fight for survival included an experimental procedure at UCLA involving the removal of a testicle, brain surgery, and grueling chemotherapy treatments. Against seemingly insurmountable odds, Lance not only survived but sought to reclaim his former glory by winning the Tour de France as a testament to his enduring spirit. His 1999 victory was particularly astonishing for a cyclist who was not previously recognized as a climber, demonstrating immense speed and power that defied expectations, especially as a cancer survivor.

However, Armstrong’s journey was not without controversy. A cortisone drug appeared in his urine during the 1999 race, prompting inquiries from the UCI. To evade potential repercussions, Lance’s team found a commercial brand that substantiated his use of cortisone as a remedy for a skin rash, thereby diffusing the situation at that time. Central to Armstrong’s doping narrative was Michele Ferrari, his team doctor, infamous for administering performance-enhancing drugs to athletes. Having known Armstrong since 1995, Ferrari devised strategies that included switching to lower gears on mountainous terrain to lessen muscle strain while introducing drugs to increase oxygen levels in the blood, enabling endurance over extended periods. Additionally, Ferrari’s connections with UCI’s drug testing labs helped ensure Armstrong’s drug use remained below the detection threshold. Despite Ferrari’s eventual conviction for sports fraud in 2004, Armstrong persisted in publicly distancing himself from him.

In 2013, Armstrong remarked that EPO doping had gained traction in Europe during the 1980s and 1990s, necessitating his adoption of its use to remain competitive from 1995 onward, a time when EPO was undetectable in urine tests. As testing methods advanced, Ferrari encouraged Armstrong to take part in blood transfusions—removing blood prior to a race and reintroducing it just before—thereby boosting red blood cell count without leaving traces.

In 2008, Armstrong aimed for a commendable return to cycling, determined to win the Tour de France and silence his critics regarding the legitimacy of his seven titles. However, complications arose when a former teammate, previously implicated in doping in 2006, sought a position on his team but was turned away in efforts to portray a “clean team.” This former teammate was privy to the extent of Lance’s drug usage and ultimately played a role in his downfall. As the 2009 Tour de France commenced, while initially positioned 10th after stage 1, Armstrong climbed quickly to second place by stage 2. The narrative also introduces a former teammate, Frankie, now a sports reporter, with whom Lance maintained a fragile connection during this period. After having testified against Armstrong in 2006 alongside his wife, the couple found themselves ostracized from the cycling community. Betsy, Frankie’s wife, became increasingly obsessed with exposing Armstrong’s deceit, ultimately rallying support from other former teammates, forming a coalition against him.

As the investigation deepened, Lance’s legal team retaliated with extensive lawsuits against his accusers, often using financial leverage to intimidate them into silence. Critics also alleged that UCI’s president, Verbruggen, was complicit in protecting Armstrong, hinting at a mutual financial interest in sustaining his image as a champion of the sport. By stage 15 of the 2009 race, Lance found himself 42 seconds behind Contador, who wore the yellow jersey. Despite his relentless efforts, he finished third, leading him to contemplate the integrity of his clean race in 2009 as validation for his previous accomplishments. However, subsequent investigations raised new doubts regarding potential blood transfusion use during that very race.

Ultimately, the revelations from the 2009 Tour ignited a torrent of testimonies from critics fueled by a desire to clarify the reality of Armstrong’s earlier races, demolishing the facade he had constructed. The burden of truth became too heavy to maintain, paving the way for the explosive Oprah interview in 2013. Following these astonishing admissions, Lance Armstrong faced a lawsuit from the US Postal Service, his sponsor during his iconic wins, for a staggering $100 million, and was subsequently banned from all sports for life by the World Anti-Doping Agency.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for The Armstrong Lie

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from The Armstrong Lie. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Cars Featured in The Armstrong Lie

Explore all cars featured in The Armstrong Lie, including their makes, models, scenes they appear in, and their significance to the plot. A must-read for car enthusiasts and movie buffs alike.

The Armstrong Lie Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

The Armstrong Lie Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for The Armstrong Lie across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

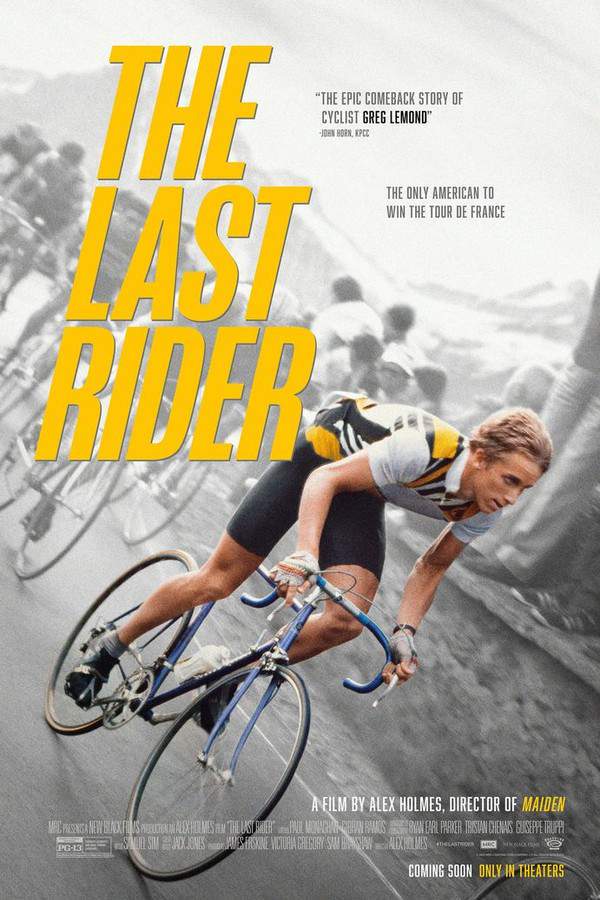

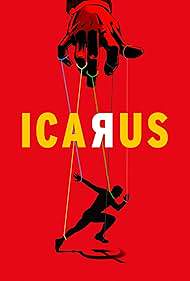

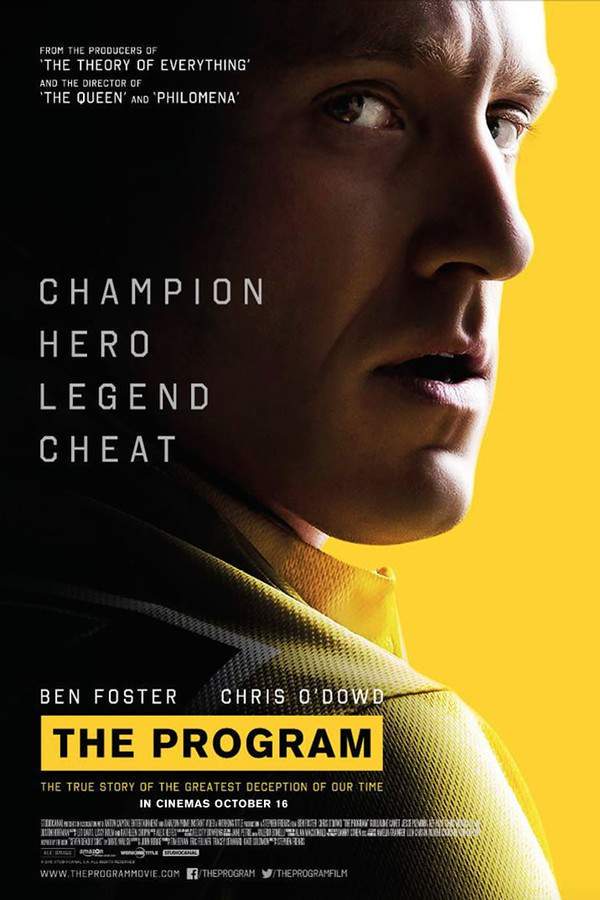

Similar Movies To The Armstrong Lie You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.