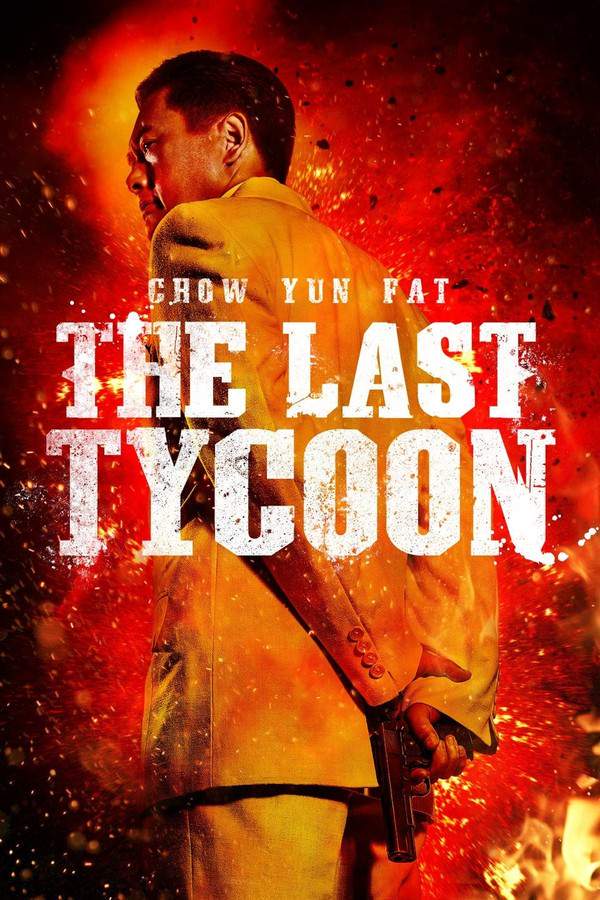

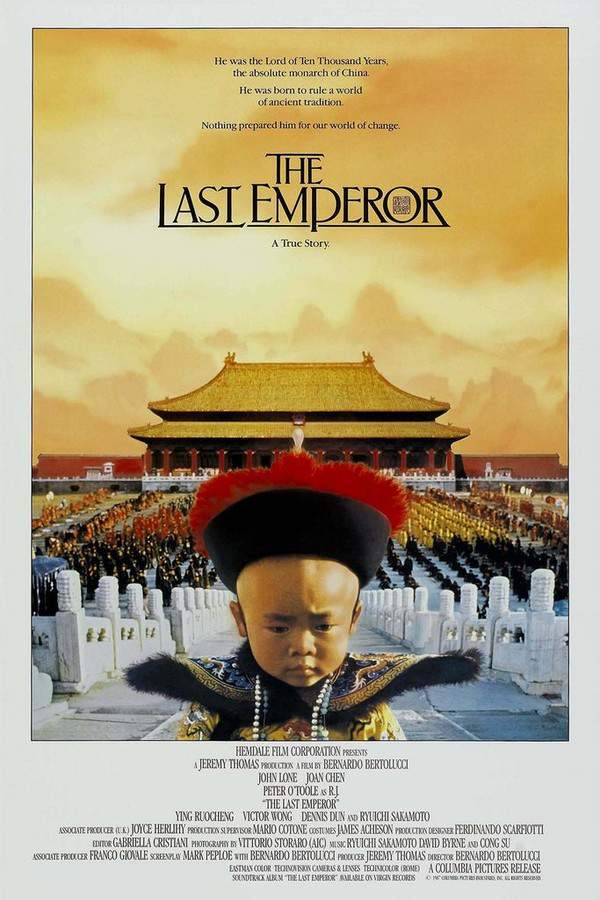

The Last Emperor 1987

This epic biographical drama chronicles the life of China's last emperor, Pu Yi, portrayed by John Lone. The film explores his privileged upbringing within the Forbidden City, showcasing the opulence and grandeur of imperial life. It follows his journey through the dramatic changes in China, from the fall of the Qing Dynasty to his imprisonment and subsequent rehabilitation as a war criminal in 1950. Through Pu Yi’s experiences, the film offers a poignant look at the collapse of an empire and the shifting dynamics of power.

Does The Last Emperor have end credit scenes?

No!

The Last Emperor does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of The Last Emperor

Explore the complete cast of The Last Emperor, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch The Last Emperor online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for The Last Emperor

See how The Last Emperor is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where The Last Emperor stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

76

Metascore

8.1

User Score

%

TOMATOMETER

0%

User Score

7.7 /10

IMDb Rating

Take the Ultimate The Last Emperor Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of The Last Emperor with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

The Last Emperor Quiz: Test your knowledge on the historical drama 'The Last Emperor' and its intricate narrative of Pu Yi's tumultuous life and legacy.

Who was the last emperor of China portrayed in the film?

Pu Yi

Pu Chieh

Johnston

Empress Dowager

Show hint

Awards & Nominations for The Last Emperor

Discover all the awards and nominations received by The Last Emperor, from Oscars to film festival honors. Learn how The Last Emperor and its cast and crew have been recognized by critics and the industry alike.

42nd British Academy Film Awards 1989

Best Cinematography

Best Costume Design

Best Editing

Best Makeup and Hair

Best Original Music

Best Production Design

Best Sound

Best Special Visual Effects

The 60th Academy Awards 1988

Art Direction

Cinematography

Costume Design

Film Editing

Music (Original Score)

Best Picture

Sound

Writing (Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium)

40th Directors Guild of America Awards 1988

45th Golden Globe Awards 1988

Best Motion Picture – Drama

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for The Last Emperor

Read the complete plot summary of The Last Emperor, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

A train arrives at a North China station in 1950, where soldiers are seen everywhere. This train is transporting prisoners, all deemed war criminals. As the prisoners wait in the station, an unusual scene unfolds: four of them suddenly rise and reverently bow to a well-dressed man, John Lone. This man, known as Pu Yi, is the last emperor of China. Uncomfortable under this unexpected reverence, he soon retreats to a bathroom, locking the door behind him. In a moment of despair, he fills a sink with hot water and slits his wrists, letting his blood cloud the water.

Outside, the prison governor, played by Ruocheng Ying, insists on entering the locked bathroom, pounding on the door and calling out, “Open the door!” Pu Yi’s thoughts drift to a long-ago era—1908, when he was just a child. The Empress Dowager Cixi orders him to the Forbidden City, where he will be anointed as the new emperor. Followed by a procession, the three-year-old Pu Yi, sobbing, is handed over by his mother to his nurse, Ar Mo, who assures her, “My son is your son.”

During his investiture, the empress proclaims, “Little Pu Yi, you will be the new Lord of Ten Thousand Years. You will be the Son of Heaven.” When silence falls after the endless bows from officials and servants, a cricket chirps, and the High Tutor presents it as a gift, declaring it the emperor’s cricket.

As he grows older, Pu Yi is largely isolated, attended to by court eunuchs and servants. He reaches out to Ar Mo, crying, “I want to go home!” but finds himself trapped in a life he never chose. Fast forward to his adulthood, where his failed suicide attempt leads him to the Fushun Detention Center, where he sits in a cell haunted by memories.

His brother, Pu Chieh, visits him, prompting further reflections on their childhood. At just eight years old, Pu Yi viewed the world through the lens of an emperor, largely indifferent to his family. Even the sacred bond with his brother is questioned when Pu Chieh insists that Pu Yi is no longer emperor.

In yet another emotional plunge, the prison governor lays out the expectations for the imprisoned war criminals, demanding autobiographies confessing their crimes while Pu Yi’s mind drifts to 1919, when he met Reginald Johnston, Peter O’Toole, his tutor. Johnston wishes to cultivate a friendship rather than a hierarchical relationship; he sees the naivety hidden beneath Pu Yi’s royal facade.

Pu Yi’s life continues through turbulent kaleidoscopes of history—his marriage in 1922 to a girl named Wen Hsiu and his political entanglements with Japan, leading to a theatrical yet tragic rise to power as emperor of the puppet state Manchukuo.

As decades pass, his reality unfolds like a scripted play, where every decision he makes is woven intricately into layers of betrayal, identity crisis, and despair. In a heartbreaking moment, Pu Yi is confronted with the fallout of his past decisions during painful interrogations, all while longing for the childhood he left behind, wrapped tightly in the comforts of the Forbidden City.

Yet, by 1959, there’s a glimmer of redemption. As a chorus of prisoners, Pu Yi finds release from the chains of his past, walking into freedom at last. 1967 welcomes him to a fresh start, functioning as a gardener, where he smiles genuinely for the first time. In a poignant rediscovery, he visits his past haunts—the Forbidden City, grappling with nostalgia and loss when confronted by the realities of his long-lived tale.

Ultimately, he reflects on a life encased in the weight of meaning and responsibility, where he declares, “I was responsible for everything.” His journey culminates in serene acceptance—a blend of power lost and the quiet dignity of an ordinary existence, culminating in a gentle farewell to the vestiges of his imperial past.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

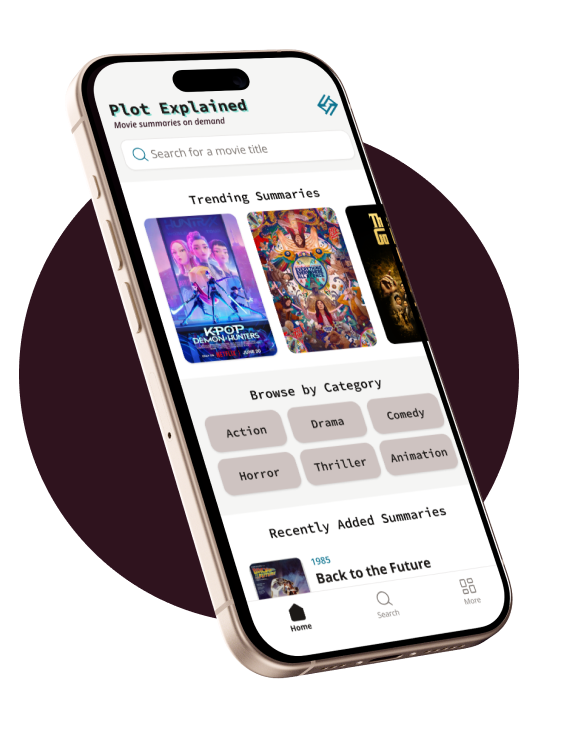

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for The Last Emperor

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from The Last Emperor. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Cars Featured in The Last Emperor

Explore all cars featured in The Last Emperor, including their makes, models, scenes they appear in, and their significance to the plot. A must-read for car enthusiasts and movie buffs alike.

The Last Emperor Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

The Last Emperor Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for The Last Emperor across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

Articles, Reviews & Explainers About The Last Emperor

Stay updated on The Last Emperor with in-depth articles, critical reviews, and ending explainers. Explore hidden meanings, major themes, and expert insights into the film’s story and impact.

Similar Movies To The Last Emperor You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.